Newest postdoctoral scholar brings international perspectives on mobility, equity & access

Since the beginning of his graduate career at Harvard University in 2017, Hao Ding has co-authored more than 25 research publications, covering a broad range of topics in transportation policy, land use planning and urban design.

After receiving his PhD from UCLA this summer, Ding is now a postdoctoral scholar at the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies. He’s well-known at ITS, where he first joined the team as a graduate student researcher in 2018. During his time as a GSR, Ding brought a core focus on equity and the built environment to his research, contributing to scholarship on issues such as the effects of design regulations on place identities in Los Angeles’s Asian American ethnoburbs and sexual harassment on public transit.

Expanding on questions of access and equity, he focused his dissertation on evaluating how embedding accessibility metrics in local and regional planning processes can better promote people’s access to jobs and other non-work opportunities. Given the technical challenges and political obstacles planning agencies have historically faced, Ding outlined a suite of policy interventions for moving the needle on accessibility.

Keep reading to learn more about Ding’s journey to contributing to more equitable transportation systems and communities in Los Angeles and beyond.

The following Q&A with Hao Ding has been edited for length and clarity.

You have lived in Xi’an (China), Singapore, London, Boston and Los Angeles. How have your experiences getting around these different places shaped your interests and values on transportation?

My experiences living in all of these different places have had significant impacts on my interests and values around transportation. In Singapore, for example, the built environment is much more transit-oriented and walkable — as compared to many places in the U.S. — that makes it easier to get around without a car.

Living in these various places has also shown me how important it is for planners to accommodate people’s needs at different stages of life. My needs as a child using transit in China, for instance, were very different from those during my time as a graduate student getting around Boston.

Moving to the U.S. for graduate school has also had a large impact on my passions around ensuring our transportation systems are working for everyone. Learning more about the ways in which the U.S.’ urban history and legacies of racist planning practices have shaped today’s transportation inequities really shifted my interests from transportation efficiency to transportation equity.

Planners and elected officials alike often use the terms “accessibility” and “mobility” interchangeably. What is the difference between the two and why did you choose to focus specifically on the concept of accessibility in your dissertation?

Accessibility and mobility are often used interchangeably because they are highly related — but with key differences. Mobility is a measure of your relative ability to move about on transportation networks (i.e., by walking, biking, driving, etc.). Accessibility, on the other hand, is a measure of the ease of reaching a destination, which can be improved by increasing mobility, but also by bringing destinations closer together. Broadly speaking, accessibility also depends on a number of other factors, including environmental barriers and perceptions of safety. And, since COVID-19, we are seeing an increase in virtual access in the forms of remote work, remote learning, telehealth, etc. I should also note that while equally important for transportation planners, accessibility in this context has a different meaning than the Americans with Disabilities Act, for instance, which focuses moreso on relative access to spaces and places for people with disabilities.

I chose to focus on accessibility in my research because it allows for a more holistic approach to understanding how people can more easily, safely, and conveniently get to where they need to be. Accessibility takes into account land use, which is a key factor to increasing people’s ability to reach destinations. For example, living in a denser, mixed-use area can mean that you have a greater variety of destinations available to you by walking, biking, or transit, than if you live in a traditional lower-density suburban area where residential and non-residential uses are often separated.

This example also demonstrates how focusing on accessibility can illuminate transportation inequities. If you live in the suburban area with access to a car, your mobility and accessibility might be high in reaching a nearby shopping center. However, if you live in the same area without access to a car, your accessibility is much lower because walking or taking transit will have greater time costs.

Your dissertation highlights historic gaps between extensive scholarship on the concept of accessibility and practice. What key lessons or actions do you hope planners and decision-makers take from your findings on planning for accessibility?

One of the primary ways agencies can plan for accessibility is through adopting accessibility metrics in local development review processes, long-range transportation and land use plans, and other key policy measures. While accessibility is a complex concept and the metrics can get very sophisticated, some are relatively easy to implement (in theory). Accessibility metrics have faced political hurdles to implementation, particularly constituent’s concerns over congestion. One reason for this is that a project that might improve regional accessibility, such as a high frequency transit station surrounded by a dense, mixed use development, can sometimes increase congestion at a local level.

At the state level, California took a major step in passing the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act (SB 375) in 2009, which requires regional governments to more holistically integrate transportation and land use strategies. States should also continue to adopt policies, such as SB 743, that shift away from conventional mobility metrics (i.e., Level of Service, or LOS) to accessibility metrics or proxies (i.e., Vehicle Miles Traveled, or VMT). Accessibility metrics help to place more emphasis on the impacts of driving (i.e., greenhouse gas emissions and walkability) rather than impacts to drivers (i.e., congestion).

At the regional level, Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) face challenges to implementing accessibility metrics because decision-making power over land use ultimately rests with local jurisdictions. However, MPOs, such as the Southern California Association of Governments, can “incentivize” localities to incorporate accessibility metrics into land use decisions and other policy measures by establishing funding priorities that award projects focused on promoting accessibility.

Given that decision-making authority over land use falls under local jurisdictions, local governments have tremendous power in shaping land use policies that support accessibility. For instance, part of the local development review process is transportation impact studies. The conventional metric for these studies is LOS, and California recently shifted to VMT. But as I show in my dissertation, accessibility metrics are better alternatives to LOS and VMT, and can be implemented relatively easily. Localities should also look to MPOs and state policies to ensure they are conforming to regional strategies for improving accessibility and equity on a systems level.

What are some current topics or issues you’re excited about researching?

I’m currently working on two projects that I am really excited about. The first is to better understand the characteristics of “supercommuters” (people who travel more than 50 miles or 90 minutes one way to get to work) in the Southern California region. This came about in part because there’s been increasing news coverage on how supercommuting is disproportionately impacting low-income families who are having to travel farther distances from where housing is cheaper to more job-rich, central areas.

The second project is looking at the equity implications of different transportation financing mechanisms, such as tolls, congestion pricing and fuel taxes. This research is especially critical as revenues from fuel taxes that go toward a range of transportation improvements are expected to decrease as electric vehicles become more prevalent. Applying an equity lens to these different financing measures will help ensure that proposed strategies do not place disproportionate cost burdens on low-income households.

How can someone who is interested in your work get in touch with you?

Feel free to email me!

Related Material

To learn more about the differences between mobility and accessibility, check out this video from our Transfers Magazine YouTube playlist.

Recent Posts

MURP student ‘speaking up’ for equity in transportation and planning

Veronica De Santos spent a semester abroad in Geneva, where she called on global leaders to invest in underrepresented voices shaping the future of sustainability and transportation.

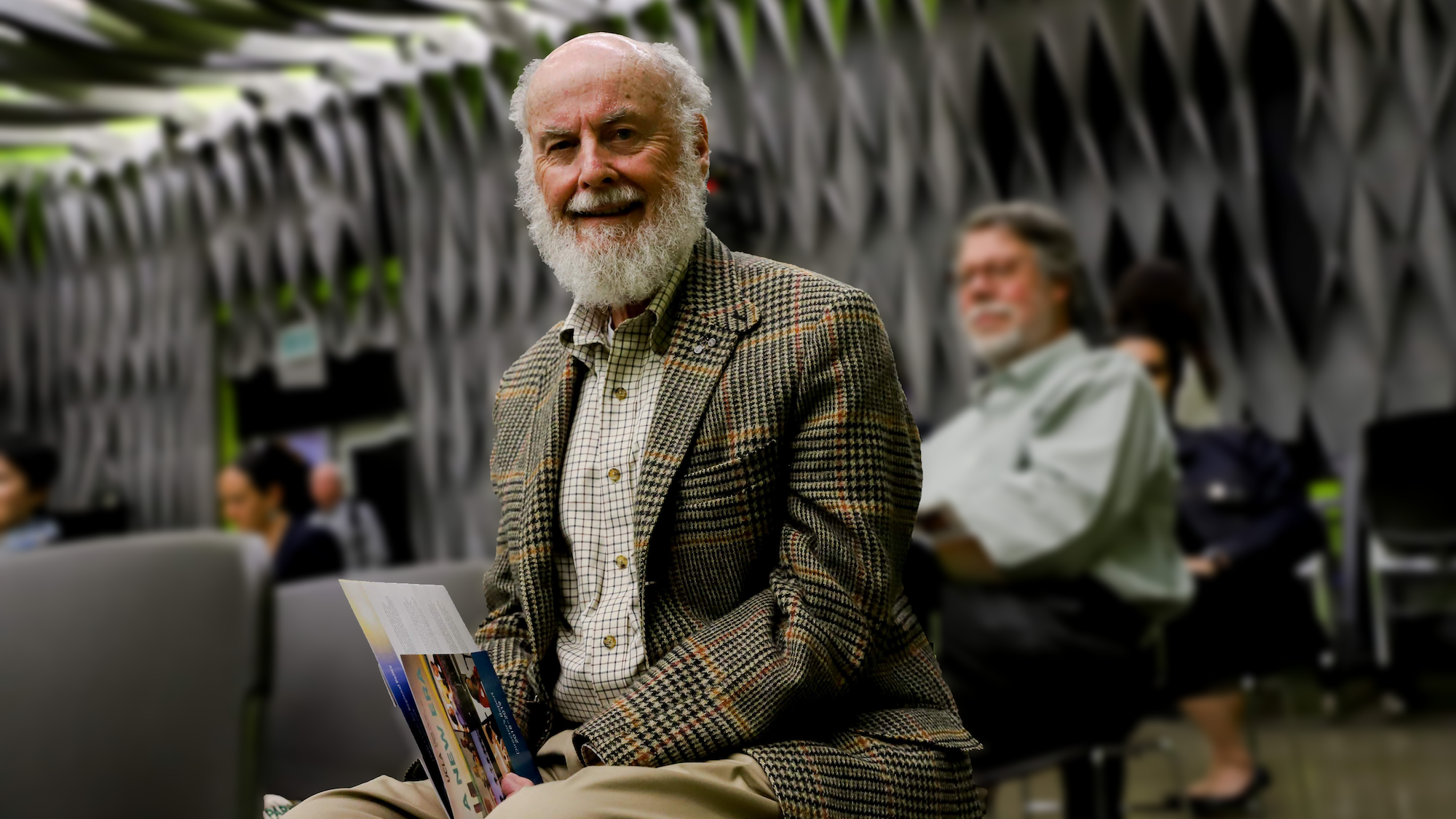

Remembering Donald Shoup

UCLA ITS’ 2nd director and a visionary scholar reshaped cities with his pioneering work on parking, inspiring legions of ‘Shoupistas’ and lasting change.