Date: February 26, 2020

Author(s): Jacob L. Wasserman, Brian D. Taylor, Evelyn Blumenberg, Mark Garrett

Abstract

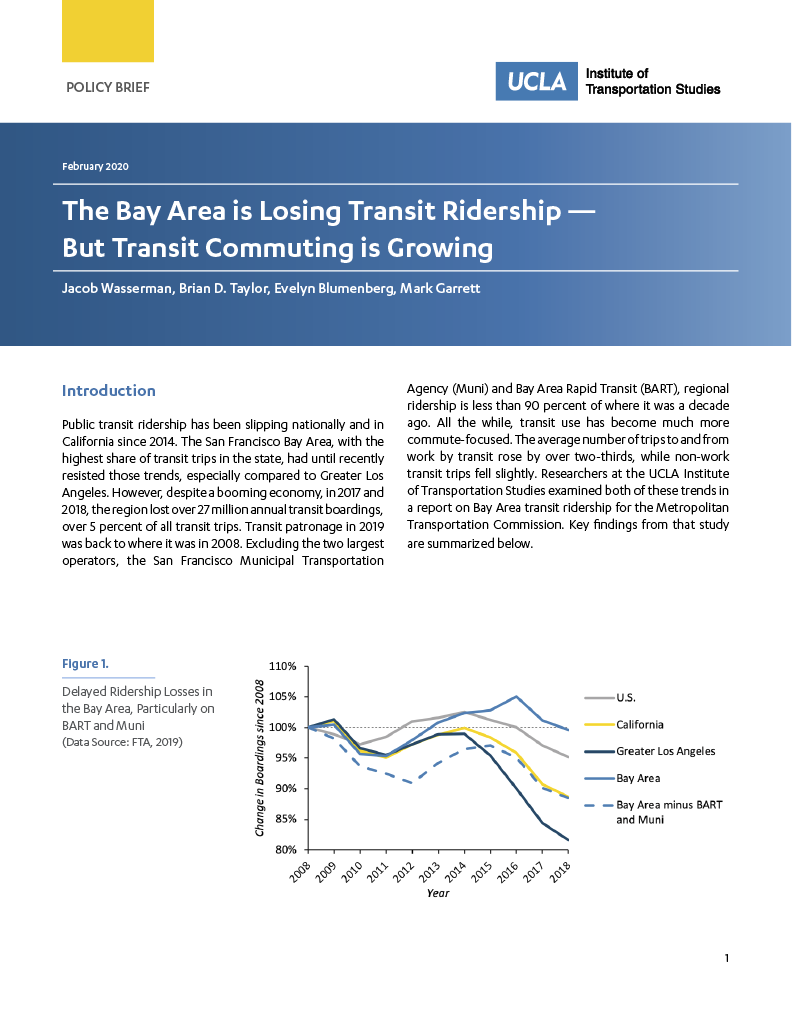

Public transit ridership has been slipping nationally and in California since 2014. The San Francisco Bay Area, with the highest share of transit trips in the state, had until recently resisted those trends, especially compared to Greater Los Angeles. However, despite a booming economy, in 2017 and 2018, the region lost over 27 million annual transit boardings, over 5 percent of all transit trips. Transit patronage in 2019 was back to where it was in 2008. Excluding the two largest operators, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (Muni) and Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), regional ridership is less than 90 percent of where it was a decade ago. All the while, transit use has become much more commute-focused. The average number of trips to and from work by transit rose by over two-thirds, while non-work transit trips fell slightly. This research finds that even before the recent dip in total ridership, individual transit use was edging downward — falling from 72 annual trips per Bay Area resident in 2008 to just 65 in 2018. Across operators, rail ridership (especially heavy rail like BART) has increased over the past decade (before the recent dip), but bus patronage has declined.

About the Project

Public transit ridership has been falling nationally and in California since 2014. The San Francisco Bay Area, with the state’s highest rates of transit use, had until recently resisted those trends, especially compared to Greater Los Angeles. However, in 2017 and 2018 the region lost over five percent (>27 million) of its annual riders, despite a booming economy and service increases. This report examines Bay Area transit ridership to understand the dimensions of changing transit use, its possible causes, and potential solutions. We find that: 1) the steepest ridership losses have come on buses, at off-peak times, on weekends, in non-commute directions, on outlying lines, and on operators that do not serve the region’s core employment clusters; 2) transit trips in the region are increasingly commute-focused, particularly into and out of downtown San Francisco; 3) transit commuters are increasingly non-traditional transit users, such as those with higher incomes and automobile access; 4) the growing job-housing imbalance in the Bay Area is related to rising housing costs and likely depressing transit ridership as more residents live in less transit-friendly parts of the region; and 5) ridehail is substituting for some transit trips, particularly in the off-peak. Arresting falling transit use will likely require action both by transit operators (to address peak capacity constraints; improve off-peak service; ease fare payments; adopt fare structures that attract off-peak riders; and better integrate transit with new mobility options) and public policymakers in other realms (to better meter and manage private vehicle use and to increase the supply and affordability of housing near job centers).