This is a web-based policy brief with an automatically generated pdf file.

Wildfire Recovery and Resilience Strategies for Resource-Constrained and Vulnerable Communities

February 28, 2025

Wildfires disproportionately impact vulnerable communities, such as low-income families, older adults, people with disabilities, and rural residents. Wildfires not only cause direct destruction, but also intensify existing social inequities (Davies et al., 2018). The primary challenges these groups face lie in inadequate transportation resources to carry out evacuations, non-resilient infrastructure, and inequitable allocations of recovery resources.

This brief synthesizes news reports, academic research, and practical case studies and recommends three priority strategies to support efforts to recover from the recent wildfires in Los Angeles County: 1) developing an inclusive evacuation system, 2) allocating resources for community recovery in a fair and equitable manner, and 3) building resilient community transportation systems for the future. These strategies can reduce social inequalities in disaster response and recovery.

Background

The January 2025 Eaton and Palisades wildfires in Los Angeles County were the first and second most destructive in California’s history (Hanna Park et al., 2025). They caused unprecedented destruction, resulting in 29 fatalities, the loss of 18,000 homes, and forced more than 200,000 residents to evacuate from the affected areas. The wildfires also caused power outages for 414,000 households, and resulted in economic damages exceeding $50 billion (Albani-Burgi, 2025). Although neither Altadena (the area most impacted by the Eaton Fire) nor the Palisades are particularly “vulnerable” communities there are considerable differences between them in their access to important resources that should be considered in crafting clear recovery strategies to protect at-risk residents.

Vulnerabilities During Evacuation

Emergency Communication Systems

One of the main problems encountered during evacuations is communicating evacuation orders and information about safe routes to residents of affected areas. Communication failures are the second most significant cause of evacuation delays after traffic congestion (Toledo et al., 2018). The 2017 Tubbs Fire in Napa and Sonoma counties highlighted the critical importance of communication systems during wildfires. Limited road networks and inadequate communication systems delayed evacuations, putting residents at greater risk (Kurhi, 2017). During the 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California agencies found that their emergency communication systems were not compatible which made it difficult to coordinate their responses when commercial phone systems went down (Comfort et al., 2018).

Similar incidents occurred during the 2025 Los Angeles wildfires which further underscore the need for robust and accurate alert systems (Baldasaro and Rozdilsky, 2025; Jarvie et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2025). In Altadena, flames erupted in Eaton Canyon around 6:30 p.m. on January 7, but while neighborhoods on the east side of town received evacuation orders at 7:26 p.m., residents on the west side did not receive an evacuation order until 3:25 a.m. the next day—hours after fires began to burn through their neighborhoods. Of the 17 people confirmed dead in the Eaton fire, all were on the town’s west side (Jarvie, 2025).

When officials attempted to send alerts to a small area near the Hearst fire, they inadvertently issued multiple erroneous emergency alerts, urging residents across Los Angeles to prepare for evacuation. These alerts, triggered by a software malfunction, sparked widespread confusion, chaos, and panic (Jarvie, 2025; Jarvie et al., 2025). False alerts like these damage the credibility of local officials, and may cause residents to be less likely to pay attention to real alerts (Baldasaro and Rozdilsky, 2025).

Evacuation Strategies

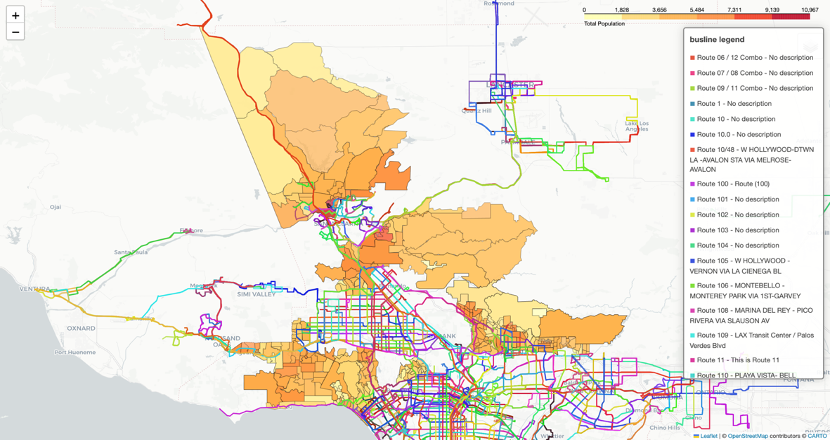

The strategies employed to physically evacuate residents from threatened areas can also produce disparities. Emergency response systems that rely on individuals using their private vehicles to evacuate may leave many vulnerable groups stranded in high-risk areas during critical evacuation periods (Bish, 2011). Households that depend on public transportation or government-arranged transit often experience delays in their evacuations . As shown in Figure 1, even in evacuation-mandated areas with high population densities, the number of public transit routes is significantly lower than in other areas of Los Angeles. (Goddard, 2024).

Figure 1: Wildfire Evacuation Zones, Population Distribution, and Bus Lines

Destructive Impacts

Minority communities are more vulnerable to the effects of wildfires. Latino communities, for example, face heightened risks due to pre-existing health disparities, economic hardships, and limited access to emergency preparedness resources (González et al., 2025) . Similarly, Black households in Altadena were disproportionately more likely to experience damage or destruction due to the Eaton Fire (Ong et al., 2025) . Addressing these interconnected vulnerabilities demands a more inclusive, community-centered approach to ensure no group is left behind during crises.

In addition to the disparities in evacuation support, current news reporting suggests that Altadena residents may face unique challenges as recovery efforts continue to unfold, underscoring the importance of service agencies having clear rebuilding strategies in place for supporting fair outcomes.

Challenges During Recovery

Altadena and Pacific Palisades differ considerably in terms of access to recovery resources. For example, residents of Pacific Palisades generally have more financial means, as exemplified by residents hiring private firefighting and cleanup services (Arango and Kamin, 2025; Downing, 2025; Reinstein, 2025). In contrast, the residents of Altadena—which consists primarily of single-family homes—have significantly lower household incomes than those in Pacific Palisades, and may face more constraints obtaining resources for post-disaster recovery (Point2Homes, n.d.; U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.). Furthermore, Reuters reports that many Altadena residents feel overlooked, as limited government and insurance company support leave them struggling to secure timely assistance (Brock, 2025). According to the Associated Press, due to the increasing frequency of wildfires, hurricanes and other natural disasters, many California homeowners find it difficult to obtain affordable private insurance (Nguyễn, 2025). At the same time, there are reports of large insurance companies refusing to renew insurance policies, forcing homeowners to rely on last resort insurance such as the FAIR program. This suggests that Altadena homeowners face a long claim process and insufficient protection, deepening the recovery gap between these two communities (Blood, 2023; Ho and Nguyễn, 2025).

Infrastructure reconstruction in underserved communities significantly lags behind wealthier neighborhoods, perpetuating social inequities (Xu and Chopra, 2023). Damaged roads and disrupted public transit impede access to essential services such as healthcare, employment, and supply chains. Additionally, vulnerable groups often lack representation in recovery planning processes, leading to inequitable resource distribution and slower recovery times (Thomas et al., 2022).

Case studies from past wildfires provide critical insights into these challenges. For instance, during the Camp Fire, transportation agencies and social service organizations worked together to provide accessible transportation for displaced residents. Temporary transit routes and shuttle services connected evacuees to shelters, healthcare facilities, and employment centers (Maranghides et al., 2023). However, systemic gaps, such as delays in financial assistance and insufficient long-term housing resources, disproportionately impacted low-income and racial minority groups, revealing persistent inequities in disaster recovery (Spearing and Faust, 2020).

Indigenous communities, like many other minority groups, are disproportionately affected by natural disasters; BIPOC individuals are 50 percent more likely to experience them (Thurston, n.d.). During the 2021 Dixie Fire, also in Northern California and one of the largest wildfires in California history (Bermel, 2021), indigenous communities in the affected regions faced unique challenges, including limited access to culturally appropriate recovery resources and prolonged displacement due to the destruction of tribal lands (Dybwad, 2023).

A comparison of the 2025 Los Angeles wildfires with past fire disasters highlights these persistent disparities. Latino and Black communities often experience slower repairs to infrastructure and inadequate recovery aid relative to their needs (González et al., 2025; Ong et al., 2025). These disparities highlight the urgent need for improving transportation and support services and policy reform, to assure fairness in recovery outcomes.

Key Recommendations

1. Develop an Inclusive Evacuation System

-

Enhance Public Transit Evacuation Networks:

Given low private vehicle ownership in vulnerable communities, systematic planning for public transit evacuation is essential. For example, Los Angeles County could adopt a bus-based regional evacuation scheduling model (Bish 2011) to deploy buses preemptively during wildfire seasons. Further, it could establish a system whereby vulnerable residents could register for special assistance during evacuations through community centers, medical institutions, and schools. This could identify carless households and individuals with disabilities, and enable buses to be used more efficiently during emergencies to better service the community. GPS-based geofencing technology can automatically distribute ride discounts during evacuation alerts though passengers’ smart devices. Additionally, we recommend that the government collaborate with companies like Uber and Lyft to provide prioritized ride services for high-risk groups (e.g., low-income families, older adults) (Wong et al., 2020).

-

Strengthen Real-Time Emergency Communication:

Develop a multi-level warning system:

-

- Technical Level: Deploy solar-powered or generator-driven emergency broadcast systems (e.g., radio towers) in remote communities to ensure voice alerts during power outages. Implement stricter geofencing protocols and periodic system tests to minimize false alarms.

- Community Level: Initiate informal communication networks to fill gaps in network blind spots (Elhami-Khorasani et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2024). Establishing a “Community Emergency Liaison” system that can recruit and train local volunteers (e.g., retired firefighters, teachers, community leaders) to use low-tech tools (e.g., flyers, whistles) and adaptive transportation (e.g., motorcycles) to spread messages can complement existing alert systems.

- Cultural Level: Address language and cultural barriers in immigrant communities by providing emergency messages in multiple languages (e.g., Spanish, Chinese). Utilize social media platforms like TikTok, X, and Instagram, as well as community organization networks, and disseminate multilingual evacuation guides tailored to the target audience.

2. Establish Strategies for Fairness in Distributing Community Recovery Resources

- Rapid Repair of Critical Transportation Infrastructure:

Post-disaster reconstruction should prioritize repairing transportation nodes that connect vulnerable communities to critical services, such as hospitals and food distribution centers. To ensure equity, a monitoring system should be established to track recovery progress toward increasing accessibility across different communities. Ongoing monitoring allows for adjustments to ensure fairness throughout the rebuilding process.

- Utilize Private Business to Support Recovery:

Private business can supplement disaster recovery efforts by leveraging their networks and resources. For instance, Airbnb’s Open Homes program has provided free temporary housing for displaced individuals and relief workers (Airbnb, 2018). Similarly, ride-sharing companies like Uber and Lyft have offered free or discounted rides to evacuation centers during disasters, aiding those without access to personal vehicles (Weaver, 2025). Logistics companies, including FedEx and UPS, have partnered with non-governmental agencies (NGOs) to deliver emergency supplies, such as water purification devices and generators, to remote communities affected by disasters like the Nepal Earthquake (Norman, 2016). These initiatives demonstrate the potential for private companies to address critical needs in housing, transportation, and logistics, thereby enhancing recovery outcomes for affected communities.

3. Build Resilient Community Transportation Systems

- Enhance Multimodal Transportation Redundancy:

Strengthening the coordination between multimodal transportation systems is essential to improve evacuation efficiency. Multimodal options significantly enhance system resilience (Blum and Eskandarian, 2004; Xu and Chopra, 2023). Customized transportation strategies for vulnerable households, including low-income families, older adults and unhoused people, such as on-demand large shuttle buses and vans can quickly adapt to changing evacuation needs (Dulebenets et al., 2019). As the LA fires dramatically demonstrated, personal vehicles may be destroyed or rendered inoperable, leaving their owners suddenly carless. This risk intensifies the need for robust public transit options and emergency mobility services to ensure no one is stranded during an evacuation. We recommend enhancing the resilience of transportation systems to natural disasters by improving transportation hubs, optimizing transfer facilities, and ensuring basic evacuation functions even during situations where there is only minor infrastructure damage. In additional, “aerial evacuation corridors” should be established by adding helicopter landing pads along mountainous highways to evacuate high-risk populations during emergencies.

- Foster Community Participation in Planning:

Community involvement is indispensable in the planning process. Socioeconomic conditions, transportation accessibility, and community connections collectively influence evacuation decisions (Wambura and Wong, 2025). Thus, transportation planning must consider community-specific needs to avoid one-size-fits-all solutions, especially for vulnerable groups. This includes understanding different groups’ transportation patterns, establishing effective multilingual communication mechanisms, and ensuring community representation in decision-making. Specific outreach measures, such as establishing designated pick-up points to transport residents without other means and collaborating with local shelters to reach unhoused persons, should be integrated to address the unique challenges faced by people experiencing homelessness, and those who have lost their vehicles during a disaster. A thorough understanding of community needs can lead to more inclusive and effective emergency transportation planning, and limit irreparable harm to vulnerable communities.

Conclusion

Wildfire recovery is not only about infrastructure reconstruction but also a test of systemic resilience, particularly for resource-constrained, vulnerable communities. Strengthening multimodal transportation integration, enhancing public transit interconnectivity, and implementing robust monitoring mechanisms can significantly shorten recovery periods for vulnerable communities and reduce future disaster risks. Through collaboration, community engagement, and data-driven decision-making, Los Angeles County agencies, and other disaster recovery service agencies across the region, can better protect vulnerable populations and enhance resilience to future disasters.

References

Airbnb. (2018). UPDATE: Airbnb Activates Open Homes Program Amidst California Wildfires. Airbnb Newsroom, November 12. https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-activates-open-homes-program-amidst-california-wildfires/

Albani-Burgio, P. (2025, January 9). As fires rage in LA, here is where power is out in and around the Coachella Valley. Palm Springs Desert Sun. https://www.yahoo.com/news/fires-rage-la-where-power-173658043.html

Arango, T., and Kamin, D. (2025). ‘Will Pay Any Amount’: Private Firefighters Are in Demand in L.A. The New York Times, January 12. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/12/us/private-firefighters-la-wildfires.html

Baldasaro, D., and Rozdilsky, J. L. (2025). False Alerts—Like the One Sent During the Greater Los Angeles Wildfires—Can Undermine Trust and Provoke Anxiety. The Conversation, January 14. http://theconversation.com/false-alerts-like-the-one-sent-during-the-greater-los-angeles-wildfires-can-undermine-trust-and-provoke-anxiety-247186

Bermel, C. (2021). Dixie Fire Becomes Largest Single Wildfire in California History. POLITICO, August 6. https://www.politico.com/states/california/story/2021/08/06/dixie-fire-becomes-largest-single-wildfire-in-california-history-1389651

Bish, D. R. (2011). Planning For a Bus-Based Evacuation. OR Spectrum, 33(3), 629–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00291-011-0256-1

Blood. (2023). California Insurance Market Rattled by Withdrawal of Major Companies. AP News, June 5. https://apnews.com/article/california-wildfire-insurance-e31bef0ed7eeddcde096a5b8f2c1768f

Blum, J. J., and Eskandarian, A. (2004). The Impact of Multi-Modal Transportation on the Evacuation Efficiency of Building Complexes. Proceedings. The 7th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (IEEE Cat. No.04TH8749), 702–707. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITSC.2004.1398987

Brock, J. (2025). Fire Survivors Feel Forgotten. Reuters, November 1. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/far-hollywoods-wealth-los-angeles-fire-survivors-feel-forgotten-2025-01-10/

Comfort, L., Soga, K., Stacey, M., McElwee, M., Ecosse, C., Dressler, J., and Zhao, B. (2018). Collective Action in Communities Exposed to Recurring Hazards. Natural Hazards Center, November 8, 2018. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/collective-action-in-communities-exposed-to-recurring-hazards

Davies, I. P., Haugo, R. D., Robertson, J. C., and Levin, P. S. (2018). The Unequal Vulnerability of Communities of Color to Wildfire. PLOS ONE, 13(11), e0205825. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205825

Downing, J. (2025,). LA Millionaires Shell Out For $2,000-An-Hour Private Firefighters as Overwhelmed City Abandons Neighborhoods to the Flames. New York Post, January 13. https://nypost.com/2025/01/12/us-news/la-millionaires-shell-out-for-2000-hr-private-firefighters/

Dulebenets, M. A., Pasha, J., Abioye, O. F., Kavoosi, M., Ozguven, E. E., Moses, R., Boot, W. R., and Sando, T. (2019). Exact And Heuristic Solution Algorithms for Efficient Emergency Evacuation In Areas With Vulnerable Populations. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 39, 101114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101114

Dybwad, A. (2023). How Wildfires Affect Indigenous Communities. PurpleAir, August 22. https://www2.purpleair.com/blogs/blog-home/how-wildfires-affect-indigenous-communities

Elhami-Khorasani, N., Kinateder, M., Lemiale, V., Manzello, S. L., Marom, I., Marquez, L., Suzuki, S., Theodori, M., Wang, Y., and Wong, S. D. (2023). Review of Research on Human Behavior in Large Outdoor Fires. Fire Technology, 59(4), 1341–1377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-023-01388-6

Goddard, T. (2024). Transit Agencies and Wildfire Evacuation. Natural Hazards Center. https://hazards.colorado.edu/weather-ready-research/transit-agencies-and-wildfire-evacuation

González, S., Pech, C., Ong, P. M., and Kochaphum, A. (2025). Wildfires and Latino Communities. Latino Policy & Politics Institute, January 14. https://latino.ucla.edu/research/wildfires-and-latino-communities/

Hanna Park, J. Y., Tsui, K., Radford, A., Rose, A., Mascarenhas, L., Boyette, C., Romine, T., Watson, M., Tucker, E., Jackson, A., and CNN. (2025). Live Updates: Los Angeles Battles Palisades and Eaton Fires as California Struggles With Containment Efforts. CNN, January 14. https://www.cnn.com/weather/live-news/los-angeles-wildfires-palisades-eaton-california-01-14-25-hnk/index.html

Ho, S., and Nguyễn, T. (2025,). California’s Insurance Crisis Leaves Neighbors Facing Unequal Recovery After Wildfires. AP News, May 2. https://apnews.com/article/california-wildfires-home-insurance-fair-plan-b545beb6c8d287eba852f9c1b1d1e504

Jarvie, J. (2025). L.A. County’s Evacuation Alert System Broke Down During Fires. It’s Part of a Larger Problem. Los Angeles Times, January 24. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2025-01-24/california-wildfires-evacuation-alerts-mistakes

Jarvie, J., Toohey, G., and Castleman, T. (2025). Faulty Evacuation Alerts Woke Angelenos in a Panic. What’s Wrong with L.A.’S Emergency System? Los Angeles Times, January 9. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2025-01-09/emergency-alert-text-message-los-angeles-fire

Kurhi, E. (2017). Wine Country Fires: Why Didn’t Sonoma County Send a Cellphone Alert? The Mercury News, October 12. https://www.mercurynews.com/2017/10/12/tubbs-fire-why-didnt-sonoma-county-send-a-cellphone-alert/

Maranghides, A., Link, E., Brown, C. U., Walton, W. D., Mell, W., and Hawks, S. (2023). A Case Study of the Camp Fire—Notification, Evacuation, Traffic, and Temporary Refuge Areas (NETTRA). NIST. https://www.nist.gov/publications/case-study-camp-fire-notification-evacuation-traffic-and-temporary-refuge-areas-nettra

Nguyen, C. (2025). ‘Not Human Driven’: Here’s Why Erroneous Evacuation Alerts Were Sent in LA County. NBC Bay Area, January 10. https://www.nbcbayarea.com/california-3/emergency-evecuation-alerts-error-los-angeles/3757527/

Nguyễn, T. (2025). How the Wildfires in the Los Angeles Area Could Affect California’s Home Insurance Market. AP News, January 10. https://apnews.com/article/california-wildfires-los-angeles-insurance-6fbb51bd3060743da0638baf4cf2845d

Norman, H. (2016). FedEx Recognized for Disaster Response Efforts in Nepal. Parcel and Postal Technology International, November 24. https://www.parcelandpostaltechnologyinternational.com/news/business-diversification/fedex-recognized-for-disaster-response-efforts-in-nepal.html

Ong, P. M., Pech, C., Frasure, L., Comandur, S., Lee, E., and González, S. R. (2025). LA Wildfires: Impacts on Altadena’s Black Community. UCLA Bunche Center, January https://bunchecenter.ucla.edu/wildfires-altadena-black-community/

Point2Homes. (n.d.). Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, CA Household Income, Population & Demographics | Point2Homes. Retrieved February 22, 2025, from https://www.point2homes.com/US/Neighborhood/CA/Los-Angeles/Pacific-Palisades-Demographics.html

Reinstein, J. (2025). Private Firefighters Spark Controversy Amid Devastating LA Fires. ABC News, January 14. https://abcnews.go.com/US/private-firefighters-spark-controversy-amid-devastating-la-fires/story?id=117626262

Spearing, L. A., and Faust, K. M. (2020). Cascading System Impacts of the 2018 Camp Fire in California: The Interdependent Provision of Infrastructure Services to Displaced Populations. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 101822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101822

Sun, Y., Forrister, A., Kuligowski, E. D., Lovreglio, R., Cova, T. J., and Zhao, X. (2024). Social Vulnerabilities and Wildfire Evacuations: A Case Study of the 2019 Kincade Fire. Safety Science, 176, 106557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2024.106557

Thomas, A. S., Escobedo, F. J., Sloggy, M. R., and Sánchez, J. J. (2022). A Burning Issue: Reviewing the Socio-Demographic and Environmental Justice Aspects of the Wildfire Literature. PLOS ONE, 17(7), e0271019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271019

Thurston, I. (n.d.). The Impact of Wildfires on Indigenous Communities. Retrieved February 11, 2025, from https://www.theindigenousfoundation.org/articles/the-impact-of-wildfires-on-indigenous-communities

Toledo, T., Marom, I., Grimberg, E., and Bekhor, S. (2018). Analysis of Evacuation Behavior in a Wildfire Event. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, 1366–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.03.033

United States Census Bureau. (n.d.). U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Altadena CDP, California. Retrieved February 22, 2025, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/altadenacdpcalifornia/PST045223?#qf-flag-X

Wambura, V., and Wong, S. D. (2025). Wildfire Evacuation Choice-Making among Underserved Groups in Alberta and British Columbia. ERA, January 1. https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-pxv0-my29

Weaver, S. (2025). Uber, Lyft Offering Free Rides to Evacuees Impacted By Los Angeles Wildfires FOX 11, January 8. https://www.foxla.com/news/uber-offering-free-rides-evacuees-los-angeles-wildfires

Xu, Z., and Chopra, S. S. (2023). Interconnectedness Enhances Network Resilience of Multimodal Public Transportation Systems for Safe-To-Fail Urban Mobility. Nature Communications, 14(1), 4291. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39999-w

CITATION

Bills, T.S. (2025). Wildfire recovery and resilience strategies for resource-constrained and vulnerable communities. UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies. https://www.its.ucla.edu/publication/wildfire-recovery-and-resilience-strategies-for-resource-constrained-and-vulnerable-communities

Research presented in this policy brief was made possible through funding received by the University of California Institute of Transportation Studies (UC ITS) from the State of California through the Public Transportation Account and the Road Repair and Accountability Act of 2017 (Senate Bill 1). The UC ITS is a network of faculty, research and administrative staff, and students dedicated to advancing the state of the art in transportation engineering, planning, and policy for the people of California. Established by the Legislature in 1947, the UC ITS has branches at UC Berkeley, UC Davis, UC Irvine, and UCLA.

PROJECT ID: LA2512